aggra-guide

Memoization

At a previous job, my organization used an architecture that relied heavily on memoization. Because of how we used it, it crippled our ability to make quick changes in a modular fashion. This wiki aims to describe the properties of memoization and what ultimately failed for us.

Definition

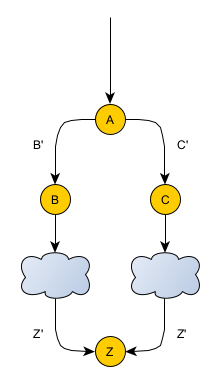

What do I mean by “memoization”? Wikipedia defines it here. To summarize, take a look at the diagram above. It’s a call graph (all arrows are in the direction of the request/call). It shows some unknown caller calling function A. A calls two other functions, B and C, with inputs B’ and C’, respectively. At that point, B and C call some arbitrary network of function calls. The networks can be completely separate or overlap in some way… it doesn’t matter. At some point, each of those networks call function Z separately but with the same input Z’. Memoization is the feature such that function Z only runs once. If in the future, another function calls Z within the same operational context with the same input, Z will return the response it previously calculated (or is currently in the process of calculating). (“Operational context” means the conditions under which the same input-to-output mapping/memory is expected to apply.)

Memoization Motivations

Memoization is used primarily for four reasons:

- Cost – a function call may be expensive: high CPU, high latency, or really any large resource usage. Memoization helps reduce this cost by only performing the function at most once within the same operational context.

- Modularity – different code locations may want to be kept as isolated as possible. In the diagram above, imagine that each caller to Z wants to call Z arbitrarily, without negotiating with any of the other callers. Memoization helps allow this, so long as each caller ends up making the same call when expected.

- Latency – similar to the last point, by avoiding negotiation, by starting the call as quickly as possible, and by making use of any previous calls; each caller tends to get its result as quickly as possible.

- Data consistency – data can change over time. For a given operational context, a system may desire that the same snapshot-in-time of the data is used. Memoization can help achieve this goal by avoiding multiple lookups or computations of that data.

Problems

I’m going to argue that memoization can go wrong when there’s an over-reliance on it working and when factors play together to make it more likely to fail. In the discussion that follows, I’m going to assume that the memoization framework itself works perfectly (i.e. given the same input, the function will only run once) and instead focus on when constructing the input itself can diverge.

When it’s critical that a function should perform its logic only once in a given operational context, that means it’s critical that every caller agree what the input should be. Each caller that uses a different input will result in the function performing its logic another time. A good example to look at is making an external service call. Different code locations may make the same service call and rely on memoization to make sure the external service is called only once. What can happen when things go wrong? For the caller, multiple calls might cause increased latency and data-inconsistencies. For the service called, multiple calls might overwhelm them: each different input from a caller would result in an increasing multiplication factor of services calls: two different inputs could mean 2 times the calls, 3 could mean 3, and so on.

What are the factors that could cause the inputs to be different in the same operational context?

- Difficulty of constructing input

- Larger inputs – the larger and more intricate the input is, the more likely it is to differ in any given part.

- More-complex inputs – the more complex it is to calculate an input, the more likely that different callers will get it wrong/disagree.

- Changes to the input – when changes to input are necessary (e.g. a new field is required or an existing field needs to be changed), some callers may end up changing their input in different ways or not at all.

- More times input is calculated – the more times the input is calculated, the more likely it is that one of those calculations will disagree.

- Modularity/independence of the callers

- More callers – the more callers a function has, the more likely it is that one of them will disagree.

- More owners – the more distinct owners who call a function, the more likely that they will do something different from one another. (An “owner” means some organization that controls one or more callers.)

- Larger separation between callers – the larger the separation between the last common point (A in the diagram above) and the function callers (callers of Z in the diagram above), the less obvious it will be that callers are even participating with others in memoization. Without that knowledge, callers will be less likely to maintain that contract. In addition, larger separations mean more intermediate steps that input has to pass through before reaching the actual function callers. This increases the likelihood that the data necessary to construct the input will be missed or mis-calculated along the way.

- More temporal independence – the more freedom given to different callers to differ over time, the more difficult it is to keep them in sync. That is, if callers are allowed to make changes independently, but there’s no guarantee that the changes will be visible at the same time, then there will exist a period where the input may be different.

- Complexity of the memoization framework – the more complex the framework is that provides the memoization feature, the more effort it will take to debug issues when it isn’t working as expected. Depending on the cost, organizations may just end up living with any failures.

(An interesting thing to note here is that modularity is both one of the reasons that memoization is used and one of the reasons that it can fail.)

Mitigations

What are some of the different ways we can mitigation these problems?

Simple, Obvious

A simple, obvious step would be to focus on each factor and reduce its individual impact.

- Larger inputs – make the inputs smaller

- More-complex inputs – make the inputs simpler

- Changes to the input – avoid changes to input

- More times input is calculated – only calculate the input once or use a shared component to calculate the input given the same set of arguments

- More callers – reduce the number of callers

- More owners – reduce the number of owners

- Larger separation between callers – minimize the separation between callers

- More temporal independence – make the callers temporally dependent

- More complex framework – make the memoization framework simpler

Call Beforehand/No Memoization

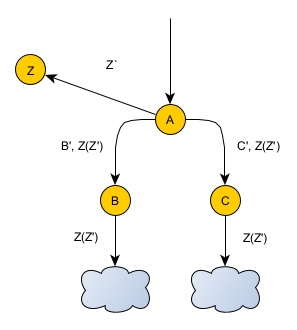

An extreme approach would be to abandon memoization entirely and call the function beforehand. This diagram illustrates this approach:

Here, A calls Z and then passes the result along to B and C, which pass it along to their network. Whoever needs the result can use it. Now there’s only a single place where Z is called.

- Pros: completely avoids the problem of a function running its logic multiple times.

- Pro/con: A must now be in charge of the conditions when the call to Z would happen. In other words, the modular logic that would have been in the old direct callers of Z is now forced to the top in A. That certainly makes the branches less modular. At the same time, it does prevent another problem: making the function call when you’re not supposed to. If Z is only supposed to be called in certain situations, and if calling it in other situations is dangerous, then moving that logic to a central authority would protect against that.

- Pro/con: every method in between A and users of Z(Z’) would now need to contain Z(Z’) as an extra parameter. On the plus side, those same methods no longer need to contain the parameters necessary to construct Z’ in the first place. So, the net effect could potentially be a wash.

- Con: a potential latency impact. Let’s say that an original caller of Z could have also called function R in parallel. Let’s say that moving the Z call to A is fine, but let’s also say it doesn’t make sense for A to own the call to R as well. If A has to wait until function Z finishes before calling B, then the call to R can only begin once Z finishes. In other words, instead of happening in parallel, the call to R must now wait for Z to finish. This problem can be avoided if the framework supports passing a future-like object representing the response from Z, rather than waiting for Z to finish. Not all frameworks support this, however (e.g. what if the the caller to R is on a different server than A).

Proxy

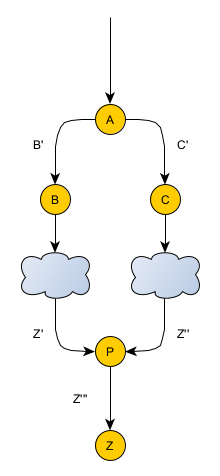

Another mitigation that addresses multiple problems is to introduce proxies in front of the function call. Here’s a diagram explaining how this would work:

Whereas the B and C networks were previously calling Z directly, they’re now calling the proxy P. The hope is that even if P is called with different inputs Z’ and Z’’, P will somehow be able to massage them into a common Z’’ input.

An example where this setup would work is well when there are going to be known changes to the input of function Z, say adding a new field. P can continue calling Z without that new field. In any call with that new field added, P will strip the field before passing it along to Z. In this way, P will allow callers to add the field to their calls at their discretion. Only when P is actually sure that all callers have been updated to add the new field will it be modified to pass the field along in its call to Z as well.

Getting Rid of Input with Potentials

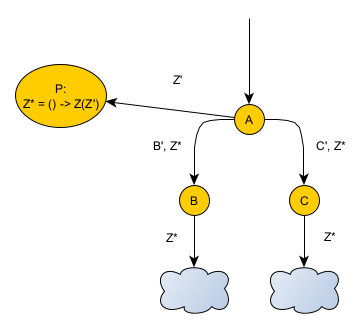

Another extreme approach, but still using memoization, is to get rid of the input entirely. This diagram illustrates this approach:

Here, A calls a new function P with input Z’. P returns a new function Z* which, when invoked, will call Z with Z’. The best word I’ve found to describe Z* is a “potential”, in that it potentially calls Z. Z* is passed down to B and C and eventually to B’s and C’s networks. Those networks can now invoke Z* with no arguments. Z*, with memoization enabled, will only ever run its logic once.

Using potentials is very similar to the previous approach, with one key difference: potentials keep the choice of the conditions when to call Z in the hands of Z’s individual callers rather than centralizing them.

- Pro: completely avoids the problem of a function running its logic multiple times.

- Pro: avoids the potential latency concern of abandoning memoization.

- Pro/con: The logic of the conditions when to call Z* are again left up to callers and not centralized. That lets callers be more independent. However, if it’s important that the function only be called in certain situations (e.g. external contributors to the call structure), and if callers can’t be relied upon to make that decision, then potentials can be more dangerous than centralizing that decision or even abandoning memoization altogether. There are a couple of different ways to mitigate this problem:

- Define protections in the potential itself. Limit it to only situations where you know it should happen.

- Only pass potentials to functions that you trust.

- Implement throttling on the potentials. Don’t let invocations exceed a certain rate.

- Pro/con: Z* and every other similar function must be added to the method signature for every method between A and users of Z*. Again, though, this impact could be reduced by the fact that those methods no longer need to pass-along the parameters necessary to construct Z’.

- Con: potentials don’t naturally extend to cross-server communication, since there’s no easy way to pass function references across the wire.

Have a Centralized Executor Execute the Dependency Graph

This is another extreme approach. Imagine the original diagram above as a dependency graph rather than a call graph. Then, imagine a centralized executor execute the graph. Clients are only responsible for defining the nodes and the wiring between nodes. The executor is in charge of executing the graph, including memoization. Using a centralized executor makes sure that the passing of arguments is controlled by a single actor.

For example, imagine that a client requests node A. The executor realizes B and C must be executed first… but before that, B’s and C’s networks must be executed first… but before that, Z must be executed first. So, the executor calls Z and then uses the result to execute the necessary nodes in B’s and C’s networks. Then, the executor executes nodes B and C with the results. Finally, the executor executes node A.

This approach has similar pros and cons as potentials. I’ll only call-out the differences here:

- Pro/con: I don’t know of an easy way or a pre-existing solution for creating such a executor. Challenges: how to declare the dependency graph in a navigable, verifiable (e.g. strong typing/compilation), and distributable way.

- Pro/con: the executor has a similar problem as potentials: when it’s important that functions are only executed in certain situations (e.g. external contributors to the graph), simply allowing any node to declare a dependency on any other node can be more dangerous than centralizing that decision or even abandoning memoization altogether. The possible solution here is similar as for potentials: restrict/minimize node visibility to only trusted clients.

- Pro: the user does not have to pass down potentials through the call stack. The centralized manager is in charge of that.

Common Theme

A common theme in almost all the mitigations I’ve looked at is that there is a loss in modularity/independence and an increase in ownership. Some central team must be responsible for deciding what it means to call the expensive function (e.g. who owns the proxy in the proxy mitigation or the potential definition in the potential mitigation). The only thing that differs is the extent to which they take ownership.

Anecdote: Architecture at Previous Job

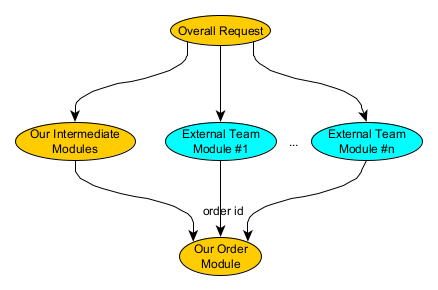

A good example of how memoization can go wrong is the architecture at my previous job.

This architecture was based around something I’ll call “modules”. For example, my team might own a module that retrieved order information based on an order id. Now, my team owned a large web page, and given the size of that system, we wanted to encourage external teams to take ownership of their own modules. This ownership included the ability to manage deployments of their modules separately from ours. For example, if an external team wanted to add a new widget to a web page, they would create and own their own module. This external team module would read the top-level request, call our order module to retrieve order information, and then use that order information to create their widget. So, there might be some n number of externally-owned modules from m external teams calling our order module in order to collaboratively create the web page that we owned. That order module was expensive, too. We could only make one call to it per top-level request, so each module implicitly had to cooperate to make sure memoization worked.

This didn’t work well. Let’s take a look at all of the factors listed above to see why:

- Larger inputs – wasn’t been an issue

- More-complex inputs – wasn’t been an issue

- Changes to the input – figuring out how to make changes across all n modules was tricky and time consuming, because each module had its own separate deployment, and so we had to do it in a backwards compatible way to avoid breaking memoization. This was true even if we just had to do something simple as adding a new constant to the call. This limited the complexity of the changes we could make. Over time, we learned to avoid changing input to the order module at all. Instead, we would jump through hoops changing the default behavior of services sitting behind that module. This was less expensive that coordinating the modification of the way the n different modules called the order module.

- More times input is calculated – we had to make a framework to ensure that input was only calculated in a single place. During initial development, we made the mistake of duplicating this logic, and one of the call sites differed slightly. That’s true even though all of the call sites at that time were internally-owned. To detect when this happens again, we asked the platform hosting our modules to create new metrics we could monitor… but that doesn’t prevent the problem from happening… it only detects that it has. Furthermore, the metric wasn’t perfect, since there were some cases where we knew we wouldn’t de-dupe (multiple calls made for multiple orders in the same top-level request).

- More callers – the inherent nature of the architecture meant making multiple callers across multiple teams. In our own code, we tried to converge the call sites but we were so afraid of breaking memoization that there were times we thought it less risky to create another call site, which increased risk, just in a different way.

- Larger separation between callers – although the diagram above shows a small distance between callers, in actuality, it was several layers deep. Furthermore, external teams had little reason to care about memoization: they just cared about calling our module to produce the code they needed.

- More temporal independence – although the platform hosting our modules had the concept of grouping them, this wasn’t supposed to apply to external teams: external teams were supposed to be allowed to deploy their modules independently. In actuality, this architecture was so brittle that we only ended up extending this model to one external team. Even then, we were paralyzed into making major changes or refactors to our modules… because separate deployments made it close to impossible and in some cases impossible to make the simplifying changes we wanted to make.

- More owners – as mentioned in the last point, we only ever extended this architecture to one external team. At that point we realized it was so brittle that we couldn’t extend it further. The goal was that hundreds of teams could develop on it.

- Complexity of the memoization framework – the complexity of the memoization framework/platform that hosted our modules isn’t really the point of this wiki. I’ll just comment that it definitely wasn’t simple and often compounded our problems.

All factors considered, the architecture’s reliance on memoization and the properties it had made it extremely fragile and incapable of meeting the goals laid out for it. There are lots of good lessons in here about how the lure of memoization can end up hurting you if applied naively.