aggra-guide

Common Node Types

Aggra ships with a set of builders to help streamline creation of common node types. This wiki describes each one, including examples of how to use it. (Users are always free to implement completely custom behavior in their nodes but should probably always start with these builders first and customize only if necessary.)

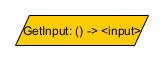

Input

Input nodes are special nodes that retrieve the input associated with the memory instance passed to a node. Input nodes make the memory instance’s input available to the rest of the graph for computation. This builder is the only way to get access to the input: users can’t build custom nodes of their own to access the input.

Here’s an example:

public class Input {

private static class TestMemory extends Memory<Integer> {

private TestMemory(MemoryScope scope, CompletableFuture<Integer> input) {

super(scope, input, Set.of(), () -> new ConcurrentHashMapStorage());

}

}

public static void main(String args[]) {

Node<TestMemory, Integer> getInput = Node.inputBuilder(TestMemory.class).role(Role.of("GetInput")).build();

System.out.println(getInput);

}

}

TestMemory is an example type of memory that returns an Integer input. GetInput is an input node associated with TestMemory that will return a TestMemory instance’s input when called with it.

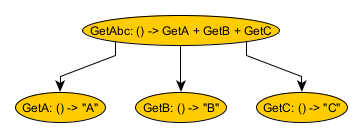

Function

FunctionNodes execute a provided function against a list of dependency nodes. There are two basic types of FunctionNodes: synchronous and asynchronous. All nodes, when called should always return their Reply (a CompletableFuture-like object) quickly; otherwise, they’ll block other nodes from running. If the function itself is quick, you should choose a synchronous node, which will execute the function inline with the invoking thread. If the function takes time, you should choose an asynchronous node, which will execute the function on another thread but concurrently return the Reply object quickly on the invoking thread.

Here’s an example:

public class Function {

private static class TestMemory extends Memory<Integer> {

private TestMemory(MemoryScope scope) {

super(scope, CompletableFuture.completedFuture(null), Set.of(), () -> new ConcurrentHashMapStorage());

}

}

public static void main(String args[]) {

Node<TestMemory, String> getA = FunctionNodes.synchronous(Role.of("GetA"), TestMemory.class).getValue("A");

Node<TestMemory, String> getB = FunctionNodes.synchronous(Role.of("GetB"), TestMemory.class).getValue("B");

Node<TestMemory, String> getC = FunctionNodes.synchronous(Role.of("GetC"), TestMemory.class).getValue("C");

Node<TestMemory, String> getAbc = FunctionNodes.synchronous(Role.of("GetAbc"), TestMemory.class)

.apply((a, b, c) -> a + b + c, getA, getB, getC);

System.out.println(getAbc);

}

}

GetA, GetB, and GetC are all 0-argument function nodes that return values. GetAbs is a 3-argument function node that accepts the results of GetA, GetB, and GetC and appends them together. The FunctionNodes class provides a variety of factory methods for n-argument functions.

The example above focuses on synchronous nodes. Asynchronous nodes are very similar, except that they also accept an additional Executor object to use for running the function. The Executor can be provided at node creation time or as the result of a dependency node during call time. FunctionNodes also provides convenient CreationTimeExecutorAsynchronousStarter and CallTimeExecutorAsynchronousStarter starter classes that bind some of the arguments necessary to create an asynchronous node. The idea is that you create a starter object and then use that multiple times to create various function nodes.

Completion Function

CompletionFunctionNodes are similar to FunctionNodes, except that the function returns a CompletionStage. This is an important characteristic, because the behavior inherent to every node returns a CompletionStage. FunctionNodes accepts a function returning an arbitrarily-typed result, and so it must wrap that result in a CompletionStage. CompletionFunctionNodes don’t need to do that wrapping. You can also view CompletionFunctionNodes as adapting some functionality that’s already multi-threaded in a compatible way into the Aggra framework.

There are two basic types of CompletionFunctionNodes: thread-lingering and thread-jumping. These types differ in what happens once the thread that executed their function has finished. The thread lingering node will lingering on the same thread and further execution will happen. The thread jumping node will jump to a new thread where further execution will happen. This is an important decision to make in a lot of CompletionStage-providing pre-existing functions. They usually have some limited, protected thread pool that completes their results they’ve returned previously. (E.g. Maybe a service call API has a function that returns a CompletableFuture immediately, listens for messages concurrently, and then completes the returned CompletableFuture from a dedicated pool.) If we continued execution on those dedicated thread, they would now be stuck executing Aggra functionality rather than doing what they were designed to do, so we should jump to a new thread before continuing.

Here’s an example based on the FunctionNodes example:

public class CompletionFunction {

private static class TestMemory extends Memory<Integer> {

private TestMemory(MemoryScope scope) {

super(scope, CompletableFuture.completedFuture(null), Set.of(), () -> new ConcurrentHashMapStorage());

}

}

public static void main(String args[]) {

Node<TestMemory, String> getA = CompletionFunctionNodes.threadLingering(Role.of("GetA"), TestMemory.class)

.getValue(CompletableFuture.completedFuture("A"));

Node<TestMemory, String> getB = CompletionFunctionNodes.threadLingering(Role.of("GetB"), TestMemory.class)

.getValue(CompletableFuture.completedFuture("B"));

Node<TestMemory, String> getC = CompletionFunctionNodes.threadLingering(Role.of("GetC"), TestMemory.class)

.getValue(CompletableFuture.completedFuture("C"));

Node<TestMemory, String> getAbc = CompletionFunctionNodes.threadLingering(Role.of("GetAbc"), TestMemory.class)

.apply((a, b, c) -> CompletableFuture.completedFuture(a + b + c), getA, getB, getC);

System.out.println(getAbc);

}

}

Everything is pretty much the same as in the FunctionNodes example, except that each function returned a CompletionStage instead of the raw value.

The example above focuses on thread-lingering nodes. Thread-jumping nodes are very similar, except that they also accept an additional Executor object to use for jumping threads. The Executor can be provided at node creation time or as the result of a dependency node during call time. CompletionFunctionNodes also provides convenient CreationTimeThreadJumpingStarter and CallTimeThreadJumpingStarter starter classes that bind some of the arguments necessary to create a thread-jumping node. The idea is that you create a starter object and then use that multiple times to create various completion function nodes.

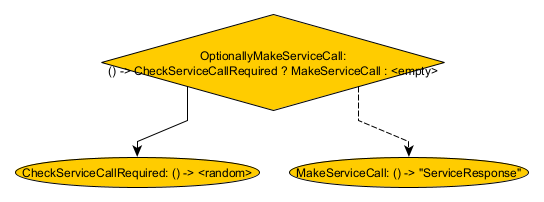

Condition

ConditionNodes evaluate conditions and then decide whether or not to call one of possibly several dependency nodes (or nothing at all). Think “if-then”, “if-then-else”, etc. Unlike FunctionNodes, which always call all of their dependency nodes right away, ConditionNodes delay calling their “branches” until after the condition is evaluated. This property allows ConditionNodes to prune parts of the graph selectively for specific graph calls.

Here’s an example:

public class Condition {

private static class TestMemory extends Memory<Integer> {

private TestMemory(MemoryScope scope) {

super(scope, CompletableFuture.completedFuture(null), Set.of(), () -> new ConcurrentHashMapStorage());

}

}

public static void main(String args[]) {

Node<TestMemory, Boolean> checkServiceCallRequired = FunctionNodes

.synchronous(Role.of("CheckServiceCallRequired"), TestMemory.class)

.get(() -> ThreadLocalRandom.current().nextBoolean());

Node<TestMemory, String> makeServiceCall = FunctionNodes

.synchronous(Role.of("MakeServiceCall"), TestMemory.class)

.getValue("ServiceResponse");

Node<TestMemory, Optional<String>> optionallyMakeServiceCall = ConditionNodes

.startNode(Role.of("OptionallyMakeServiceCall"), TestMemory.class)

.ifThen(checkServiceCallRequired, makeServiceCall);

System.out.println(optionallyMakeServiceCall);

}

}

CheckServiceCallRequired simulates a real-world condition about whether to make a service call by generating a random boolean. MakeServiceCall pretends to make that service call by returning the “ServiceResponse” value. Finally, OptionallyMakeServiceCall calls CheckServiceCallRequired to see if the service call is required; if so, then it calls MakeServiceCall; otherwise, it returns an empty response.

The example above focuses on the simplest type of condition node. Here’s a summary of all of them:

- ifThen – checks a condition to decide whether or not to call a dependency.

- ifThenElse – checks a condition to decide whether to call an “if dependendency” (if the condition is true) or an “else dependency” if the condition is false.

- select – calls a node that chooses which, of all the select node’s possible dependencies, the select node should call.

- optionallySelect – same as select, except the choosing node can also return that the optionallySelect node should call nothing.

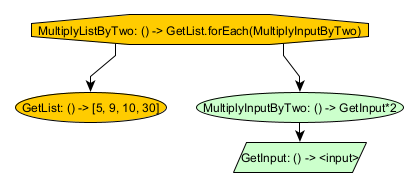

Iteration

IterationNodes iteratively call a dependency node. This is possible, because the dependency node is in another memory, and the iteration node creates a new instance of that memory for each iteration.

Here’s an example:

public class Iteration {

private static class MainMemory extends Memory<Integer> {

private MainMemory(MemoryScope scope) {

super(scope, CompletableFuture.completedFuture(null), Set.of(), () -> new ConcurrentHashMapStorage());

}

}

private static class SecondaryMemory extends Memory<Integer> {

private SecondaryMemory(MemoryScope scope, CompletionStage<Integer> input) {

super(scope, input, Set.of(), () -> new ConcurrentHashMapStorage());

}

}

public static void main(String args[]) {

Node<SecondaryMemory, Integer> getInput = Node.inputBuilder(SecondaryMemory.class)

.role(Role.of("GetInput"))

.build();

Node<SecondaryMemory, Integer> multiplyInputByTwo = FunctionNodes

.synchronous(Role.of("MultipleInputByTwo"), SecondaryMemory.class)

.apply(num -> 2 * num, getInput);

Node<MainMemory, List<Integer>> getList = FunctionNodes.synchronous(Role.of("GetList"), MainMemory.class)

.getValue(List.of(5, 9, 10, 30));

// javac (but not Eclipse) has a problem inferring type arguments when the memory factory is declared inline,

// so break it out into a separate variable definition.

MemoryFactory<MainMemory, Integer, SecondaryMemory> secondaryMemoryFactory = (scope, input,

main) -> new SecondaryMemory(scope, input);

Node<MainMemory, List<Integer>> multiplyListByTwo = IterationNodes

.startNode(Role.of("MultiplyListByTwo"), MainMemory.class)

.iterate(getList, secondaryMemoryFactory, multiplyInputByTwo)

.collectToOutputList();

System.out.println(multiplyListByTwo);

}

}

There are two memories involved here: the main memory and the secondary memory. GetInput is associated with the secondary memory and returns that memory’s input. MultiplyInputBy2 is also associated with the dependency memory and multiplies GetInput by 2. GetList is associated with the main memory and returns a predefined list of integers: [5. 9, 10, 30]. MultiplyListByTwo iterates over every element of GetList, creates a new SecondaryMemory with that element as its input, calls MultiplyInputBy, and then collects all results in a list. The result in this case would always be [10, 18, 20, 60].

The example above focuses on the most common type of iteration node. Here’s a summary of all of them:

- iterate-to-list – iterates over an iterable, creates a new memory for each element with that element as the input, calls a dependency node in that new memory and then collects the results to a list.

- iterate-to-input-to-output-map – same as iterate-to-list, except collects the results in a map of each element in the original iterable to the result it produced from the dependency node.

- iterate-to-custom – same as iterate-to-list, except allows the specification of a custom transformer to process the original list of inputs and the list of resulting outputs from calling the dependency node.

- iterate-no-input-to-list – same as iterate-to-list, except the iterable itself produces no-input memory factories that iterate-no-input-to-list uses to create the memories; the rest of the process is the same.

Memory Trip

MemoryTripNodes allow users to create new memories and call dependency nodes there or access dependency nodes in ancestor memories. We already saw how IterationNodes have memory creation built into them. There are other reasons that users might want to create new memories, though (e.g. reuse), and once you have a new memory, that new memory may need to access its ancestors.

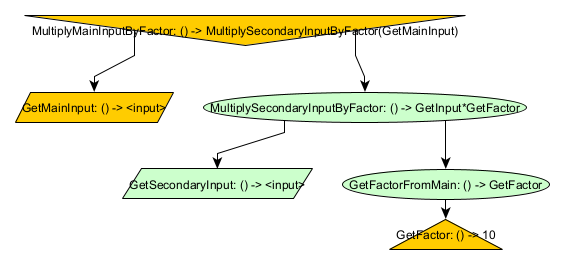

Here’s an example:

public class MemoryTrip {

private static class MainMemory extends Memory<Integer> {

private MainMemory(MemoryScope scope, CompletionStage<Integer> input) {

super(scope, input, Set.of(), () -> new ConcurrentHashMapStorage());

}

}

private static class SecondaryMemory extends Memory<Integer> {

private final MainMemory mainMemory;

private SecondaryMemory(MemoryScope scope, CompletionStage<Integer> input, MainMemory mainMemory) {

super(scope, input, Set.of(mainMemory), () -> new ConcurrentHashMapStorage());

this.mainMemory = mainMemory;

}

public MainMemory getMainMemory() {

return mainMemory;

}

}

public static void main(String args[]) {

Node<MainMemory, Integer> getFactor = FunctionNodes.synchronous(Role.of("GetFactor"), MainMemory.class)

.getValue(10);

Node<SecondaryMemory, Integer> getFactorFromMain = MemoryTripNodes

.startNode(Role.of("GetFactorFromMain"), SecondaryMemory.class)

.accessAncestorMemoryAndCall(SecondaryMemory::getMainMemory, getFactor);

Node<SecondaryMemory, Integer> getSecondaryInput = Node.inputBuilder(SecondaryMemory.class)

.role(Role.of("GetSecondaryInput"))

.build();

Node<SecondaryMemory, Integer> multiplySecondaryInputByFactor = FunctionNodes

.synchronous(Role.of("MultiplySecondaryInputByFactor"), SecondaryMemory.class)

.apply((num, factor) -> num * factor, getSecondaryInput, getFactorFromMain);

Node<MainMemory, Integer> getMainInput = Node.inputBuilder(MainMemory.class)

.role(Role.of("GetMainInput"))

.build();

Node<MainMemory, Integer> multiplyMainInputByFactor = MemoryTripNodes

.startNode(Role.of("MultiplyMainInputByFactor"), MainMemory.class)

.createMemoryAndCall(SecondaryMemory::new, getMainInput, multiplySecondaryInputByFactor);

System.out.println(multiplyMainInputByFactor);

}

}

The above example utilizes some of the same parts as the IterationNodes example. There are again two memories: the main memory and the secondary memory. This time, however, the secondary memory depends on the main memory as an ancestor. GetFactor is associated with the main memory and returns 10. GetFactorFromMain is associated with the secondary memory and calls GetFactor by accessing it in the ancestor main memory. GetSecondaryInput is associated with the secondary memory and returns that memory’s input. MultiplySecondaryInputByFactor is associated with the secondary memory and multplies GetSecondaryInput by GetFactor. GetMainInput is associated with the main memory and returns that memory’s input. Finally, MultiplyMainInputByFactor calls GetMainInput, creates a new SecondaryMemory with that value as its input, and then calls MultiplySecondaryInputByFactor. The result for this graph will be <main-input>*10.

The above example demonstrates two of the three types of MemoryTripNodes. Here’s a summary of all three:

- access-ancestor – accesses an ancestor memory and calls a dependency node there

- create-memory – calls a dependency node, creates a new memory using that dependency node result as the input, and then calls a node in the new memory

- create-memory-no-input – same as create-memory, except the new memory is supplied (either through a node or as a constant) without specifying an input.

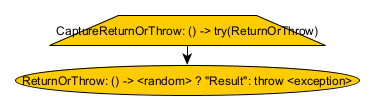

Capture Response

CaptureResponseNodes capture responses from other nodes whether those nodes succeed or fail. Normally, consumer nodes will fail if one of their dependencies fails. CaptureResponseNodes allow clients a chance to inspect those dependency failures (e.g. to take an action or suppress them).

Here’s an example:

public class CaptureResponse {

private static class TestMemory extends Memory<Integer> {

private TestMemory(MemoryScope scope) {

super(scope, CompletableFuture.completedFuture(null), Set.of(), () -> new ConcurrentHashMapStorage());

}

}

public static void main(String args[]) {

Node<TestMemory, String> returnOrThrow = FunctionNodes.synchronous(Role.of("ReturnOrThrow"), TestMemory.class)

.get(() -> {

if (ThreadLocalRandom.current().nextBoolean()) {

return "Result";

}

throw new IllegalStateException();

});

Node<TestMemory, Try<String>> captureReturnOrThrow = CaptureResponseNodes

.startNode(Role.of("CaptureReturnOrThrow"), TestMemory.class)

.captureResponse(returnOrThrow);

System.out.println(captureReturnOrThrow);

}

}

ReturnOrThrow checks a random boolean; if true, if returns “Result”; otherwise, it throws an exception. CaptureReturnOrThrow captures the response from ReturnOrThrow in a Try object. CaptureReturnOrThrow will never throw an exception, but will return either a successful or failed Try object, depending on whether ReturnOrThrow succeeds. (Make sure to read the notes in Node#call about how exceptional responses are represented in Reply objects: the Try object will never just be the raw exception thrown by ReturnOrThrow, but will instead always be wrapped in some other exception.)

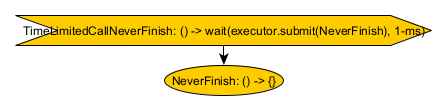

TimeLimit

TimeLimitNodes mirror a dependency node, setting time limits on how long the dependency takes to return its response and/or how long it takes the dependency to complete its response. This concept is useful to protect against unreliable/rogue nodes that may take too long doing either. Beware that, if a timeout is specified, the created time-limit node will have a DependencyLifetime of GRAPH, which as stated in the advanced wiki, takes more resources for Aggra to track. There’s also another section in that advanced wiki on handling unreliable nodes that you should look over, too, before deciding whether TimeLimitNodes is your best option given the tradeoffs.

Here’s an example:

public class TimeLimit {

private static class TestMemory extends Memory<Integer> {

private TestMemory(MemoryScope scope) {

super(scope, CompletableFuture.completedFuture(null), Set.of(), () -> new ConcurrentHashMapStorage());

}

}

public static void main(String args[]) {

ExecutorService executor = Executors.newCachedThreadPool();

Node<TestMemory, String> neverFinish = CompletionFunctionNodes

.threadLingering(Role.of("NeverFinish"), TestMemory.class)

.getValue(new CompletableFuture<>());

Node<TestMemory, String> timeboundCallNeverFinish = TimeLimitNodes

.startNode(Role.of("TimeLimitedCallNeverFinish"), TestMemory.class)

.executor(executor)

.timeout(1, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS)

.timeLimitedCall(neverFinish);

System.out.println(timeboundCallNeverFinish);

}

}

NeverFinish returns a new CompletableFuture which will never finish. (Warning: this is a demonstrative extreme case. All nodes calls should complete eventually as a best practice.) TimeLimitedCallNeverFinish calls NeverFinish on a thread provided by executor and waits for 1-ms for it to finish. If NeverFinish does finish in that time, TimeLimitedCallNeverFinish will mirror its response; otherwise, TimeLimitedCallNeverFinish will complete itself with a TimeoutExeption.

The above example demonstrates some values for the two options supported by TimeLimitNodes. Here’s a summary of all of them:

- calling-executor – the calling executor controls how the time-limit node calls the dependency. The supported values are on the caller thread directly, on a specified executor, or on an executor determined at node call time.

- timeout – the timeout controls how long the time-limit node waits for a response form the dependency. The supported values are never to timeout and a specified timeout.

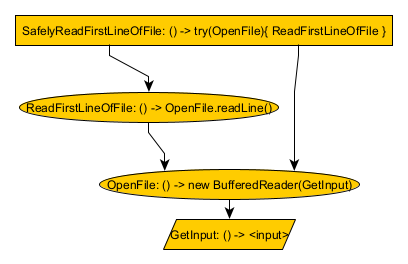

Try With Resource

TryWithResourceNodes are the Aggra equivalent of java’s try-with-resource pattern. TryWithResourceNodes call a dependency node to yield a resource (i.e. an AutoCloseable), the call another dependency node which consumes that resource, and then then call close on the resource. TryWithResourceNodes validate during graph creation time that they envelop the resource node (i.e. that the try-with-resource node consumes every consumer of the resource node, either directly or indirectly) and throw an exception if not true. This validation prevents the resource escaping somehow by having another node who’s not a dependency of the try-with-resource node call the resource node. In addition, TryWithResourceNodes validate that the resource-consuming dependency node wait for all of its dependencies to be complete before completing itself. This validation makes sure that all resource consumers are complete before the resource is closed. In combination, these validations make sure that TryWithResourceNodes behaves exactly like the Aggra-equivalent of try-with-resources (although not as obviously so since try-with-resources has the benefit of a block of code to show who all the consumers are and verify they’re completed).

Here’s an example:

public class TryWithResource {

private static class TestMemory extends Memory<String> {

private TestMemory(MemoryScope scope, CompletionStage<String> input) {

super(scope, input, Set.of(), () -> new ConcurrentHashMapStorage());

}

}

public static void main(String args[]) {

Node<TestMemory, String> getInput = Node.inputBuilder(TestMemory.class).role(Role.of("GetInput")).build();

Node<TestMemory, String> safelyReadFirstLineOfFile = TryWithResourceNodes

.startNode(Role.of("SafelyReadFirstLineOfFile"), TestMemory.class)

.tryWith(() -> openFile(getInput), TryWithResource::readFirstLineOfFile);

System.out.println(safelyReadFirstLineOfFile);

}

private static Node<TestMemory, BufferedReader> openFile(Node<TestMemory, String> getInput) {

return FunctionNodes.synchronous(Role.of("OpenFile"), TestMemory.class)

.graphValidatorFactory(TryWithResourceNodes.validateResourceConsumedByTryWithResource())

.apply(name -> callUnchecked(() -> Files.newBufferedReader(Path.of(name))), getInput);

}

private static Node<TestMemory, String> readFirstLineOfFile(Node<TestMemory, BufferedReader> openFile) {

return FunctionNodes.synchronous(Role.of("ReadFirstLineOfFile"), TestMemory.class)

.dependencyLifetime(DependencyLifetime.NODE_FOR_ALL)

.apply(reader -> callUnchecked(() -> reader.readLine()), openFile);

}

private interface IoCallable<T> {

T call() throws IOException;

}

// "Deal" with checked IOExceptions

private static <T> T callUnchecked(IoCallable<T> callable) {

try {

return callable.call();

} catch (IOException e) {

throw new RuntimeException(e);

}

}

}

GetInput reads the TestMemory’s input. OpenFile calls GetInput and then creates a new BufferedReader at that path. ReadFirstLineOfFile calls OpenFile and then reads a single line from the BufferedReader. SafelyReadFirstLineOfFile calls OpenFile followed by ReadFirstLineOfFile, and after that finished, SafelyReadFirstLineOfFile closes the BufferedReader returned by SafelyReadFirstLineOfFile. So, overall, SafelyReadFirstLineOfFile safely reads the first line of the file whose name matches the input of TestMemory.

There are only two minor variants of the TryWithResourceNodes: try-with-resource (which we saw in the above example) and try-with-resource-close-exception-transformer. This latter variant’s only difference is that it invokes an explicit exception transformer when the AutoCloseable resource’s close method throws a checked exception (in order to transform it into an unchecked exception).