aggra-guide

Motivation

This wiki walks through a motivating example for why the Aggra library exists at all.

Example

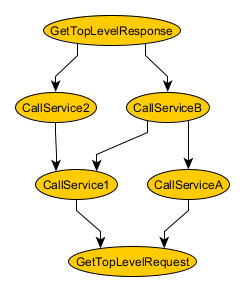

Below is a data dependency diagram for the simple example we’ll be talking about. Each node represents a function that returns a result. Each arrow represents a dependency needed to execute the function.

The example represents an implementation of a service operation. GetTopLevelRequest returns the top-level request for the operation. CallService1 calls an external service (named “1” for simplicity); it needs the TopLevelRequest to do that, which it gets from GetTopLevelRequest. And so on, and so forth. The implementations calls four external services in total: 1, 2, A, and B; each of which needs different dependencies to do that. Finally, GetTopLevelResponse depends on two service calls (2 and B) and returns the TopLevelResponse to clients who call the service operation.

Below are some common class definitions that will appear in code snippets for various approaches. For simplicity, GetTopLevelRequest is replaced by the TopLevelRequest directly. Otherwise, each class maps one-to-one to the nodes in the above dependency graph.

// Define skeletons for the main classes in the example

class TopLevelRequest {

}

class Service1 {

static ServiceResponse1 callService(TopLevelRequest request) { ... }

}

class Service2 {

static ServiceResponse2 callService(ServiceResponse1 response1) { ... }

}

class ServiceA {

static ServiceResponseA callService(TopLevelRequest request) { ... }

}

class ServiceB {

static ServiceResponseB callService(ServiceResponseA responseA, ServiceResponse1 response1) { ... }

}

class GetTopLevelResponse {

static TopLevelResponse getResponse(ServiceResponse2 response2, ServiceResponseB responseB) { ... }

}

No Futures

In this approach for implementing the service operation, we’ll use no futures at all and just call the classes directly.

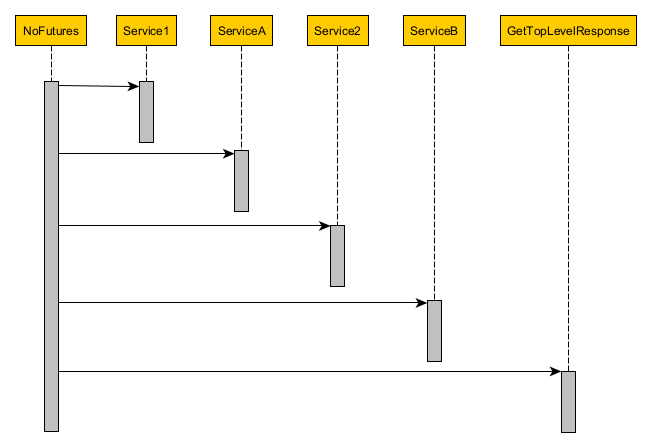

Here’s what the code and sequence diagrams look like:

public class NoFutures {

public static TopLevelResponse run(TopLevelRequest request) {

ServiceResponse1 response1 = Service1.callService(request);

ServiceResponseA responseA = ServiceA.callService(request);

ServiceResponse2 response2 = Service2.callService(response1);

ServiceResponseB responseB = ServiceB.callService(responseA, response1);

return GetTopLevelResponse.getResponse(response2, responseB);

}

}

On the plus side, the code is extremely simple. On the minus side, it’s really inefficient. From the sequence diagram, we can see how all of Service1 through GetTopLevelResponse are back-to-back sequential. This is true even though ServiceA could run in parallel with Service1 or how Service2 doesn’t need to wait until ServiceA is finished. Whether simplicity or efficiency matters more depends on the use case.

Phased Pull-Based Futures

To address the efficiency issue of the last approach, we have to find a way to execute steps in parallel. A reasonable first step in adding complexity would be to take a phased pull-based future approach. By “pull-based future”, I mean those futures where you have to pull/request the result before deciding what to do next. A good example would be any future from ThreadPoolExecutorService. In comparison, “push-based futures” themselves decide what to do next (or at least offer that ability. A good example is CompletableFuture. By “phased”, I mean dividing the program into logical phases, where one group of actions happens in the first phase, another in the second, and so on. (For comparison, we’ll examine a full-fledged, extreme, unphased approach after this one.)

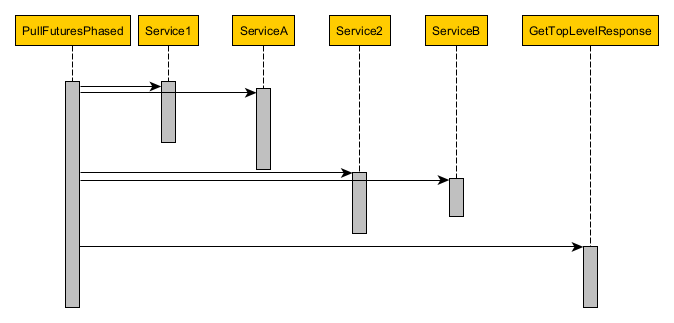

Here’s what the code and sequence diagrams look like:

public class PullFuturesPhased {

public static TopLevelResponse run(ExecutorService executorService, TopLevelRequest request)

throws InterruptedException, ExecutionException {

// Phase 1

Future<ServiceResponse1> responseFuture1 = executorService.submit(() -> Service1.callService(request));

Future<ServiceResponseA> responseFutureA = executorService.submit(() -> ServiceA.callService(request));

ServiceResponse1 response1 = responseFuture1.get();

ServiceResponseA responseA = responseFutureA.get();

// Phase 2

Future<ServiceResponse2> responseFuture2 = executorService.submit(() -> Service2.callService(response1));

Future<ServiceResponseB> responseFutureB = executorService

.submit(() -> ServiceB.callService(responseA, response1));

ServiceResponse2 response2 = responseFuture2.get();

ServiceResponseB responseB = responseFutureB.get();

// Phase 3

return GetTopLevelResponse.getResponse(response2, responseB);

}

}

On the plus side, because ServiceA can now run in parallel with Service1 and because ServiceB can run in parallel with Service2, the overall service operation will run more quickly. In addition, by grouping calls into phases, the implementation remains relatively easy for humans to understand and reason about.

On the minus side, there are still (latency) inefficiencies. For this overall request, Service2 had to wait until ServiceA was finished before it could start, even though Service2 has no dependency on ServiceA. In general, the least efficient call in each phase will determine how much of an unnecessary delay there will be until the next phase. It may not be obvious how to group calls into phases to reduce this inefficiency. There will always be a natural tendency to experiment with groups or to add “just one more phase” in an attempt to optimize. What’s worse, “the least efficient call” isn’t guaranteed to be the same for each overall request. In general, because the alignment of calls will never be perfect, a 100% optimal grouping simply won’t exist, and users will have to settle for something worse. So, this grouping process becomes more of an educated guessing game rather than pure reasoning based on dependencies.

An additional, obvious minus is the jump in complexity. Parallel execution doesn’t come for free. Users will now have to reason about two or more pieces of code executing at the same time and protect against interference (for which entire books have been written).

The last minus I want to talk about is a different kind of inefficiency: thread usage. In between phase 1 and 2, the main thread is simply waiting around, first for Service1 to finish and then ServiceA. Something similar happens after phase 2. That’s not an efficient usage of the thread (although this may change in future versions of java with project Loom). Now, the code above is a simple toy example, and a reasonable framework can be built to avoid this inefficiency, but the issue is worth pointing out.

Extreme Pull-Based Futures

To solve for the latency inefficiencies of the previous approach, a next reasonable jump in complexity is to change from a phased approach to an extreme approach: where every call happens as quickly as it can.

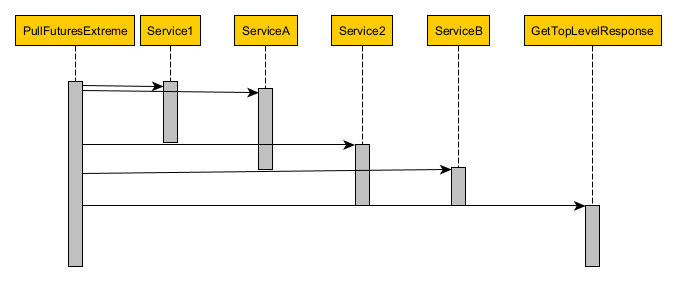

Here’s what the code and sequence diagrams look like:

public class PullFuturesExtreme {

public static Future<TopLevelResponse> run(ExecutorService executorService, TopLevelRequest request)

throws InterruptedException, ExecutionException {

Future<ServiceResponse1> responseFuture1 = executorService.submit(() -> Service1.callService(request));

Future<ServiceResponseA> responseFutureA = executorService.submit(() -> ServiceA.callService(request));

Future<ServiceResponse2> responseFuture2 = executorService.submit(() -> {

ServiceResponse1 response1 = responseFuture1.get();

return Service2.callService(response1);

});

Future<ServiceResponseB> responseFutureB = executorService.submit(() -> {

ServiceResponse1 response1 = responseFuture1.get();

ServiceResponseA responseA = responseFutureA.get();

return ServiceB.callService(responseA, response1);

});

return executorService.submit(() -> {

ServiceResponse2 response2 = responseFuture2.get();

ServiceResponseB responseB = responseFutureB.get();

return GetTopLevelResponse.getResponse(response2, responseB);

});

}

}

On the plus side, since each call happens as quickly as it can, the service operation now has a minimal latency. On the minus side, there’s a proliferation of futures: every call has to be a future, if for no other reason than not to block the main thread in case one of its dependencies isn’t finished, yet. In that same light, there’s an increase in thread inefficiency: two threads (Service2 and ServiceB) will now wait until Service1 is finished. That may seem small for this specific example, but generally speaking, whenever n calls depend on a single, other call; then n threads will be waiting for the single call to finish.

Push Futures

To address the thread inefficiencies of the previous approach, a reasonable next step would be to switch to using push-based futures.

Here’s what the code looks like (the sequence diagram is the same as before… and will be for the remaining approaches, so I won’t present it again):

public class PushFutures {

public static CompletableFuture<TopLevelResponse> run(Executor executor, TopLevelRequest request) {

CompletableFuture<ServiceResponse1> responseFuture1 = CompletableFuture

.supplyAsync(() -> Service1.callService(request), executor);

CompletableFuture<ServiceResponseA> responseFutureA = CompletableFuture

.supplyAsync(() -> ServiceA.callService(request), executor);

CompletableFuture<ServiceResponse2> responseFuture2 = responseFuture1

.thenApply(response1 -> Service2.callService(response1));

CompletableFuture<Void> both1AndA = CompletableFuture.allOf(responseFuture1, responseFutureA);

CompletableFuture<ServiceResponseB> responseFutureB = both1AndA.thenApply(ignore -> {

ServiceResponse1 response1 = responseFuture1.join();

ServiceResponseA responseA = responseFutureA.join();

return ServiceB.callService(responseA, response1);

});

CompletableFuture<Void> both2AndB = CompletableFuture.allOf(responseFuture2, responseFutureB);

return both2AndB.thenApply(ignore -> {

ServiceResponse2 response2 = responseFuture2.join();

ServiceResponseB responseB = responseFutureB.join();

return GetTopLevelResponse.getResponse(response2, responseB);

});

}

}

On the plus side, there’s no longer any thread inefficiency: push-based futures chain actions on the end of whatever thread ends up completing them (or the current thread, if the future is already complete). On the minus side, there’s some organizational overhead in creating “allOf” futures for calls with multiple dependencies. More importantly, although it’s not obvious here, push-based futures have a tendency to lose useful debugging information: specifically, the stack trace may no longer contain the cause for why the future is executing at all. E.g. it’s easy to see in the code above why ServiceB would be executed (it comes after “both1AndA”, “responseFuture2”, etc.), but the stack trace may skip all/most of that, depending on the thread that ends up running the function passed to “thenApply”.

Conditional

One assumption we’ve made so far is that every call in the graph will be run for every overall request. This may not be true. As an example, let’s consider the case where clients can request either Service2 or ServiceB.

There are a couple of things worth noting before we start. One possible strategy would be to just call every Service anyway and then only include the result in the overall response if it was requested. If you can do that, then it’s the simplest strategy. There are definitely efficiency implications, as in the worst case, you call everything but need nothing. Another possibility is that the graph is well partitioned such that each part is controlled exclusively by one condition. In that case, each partition would, by itself, be another micro-version of the approaches we’ve already gone through. Moving forward, I’m going to assume that we only want a single service call (presumably because they’re expensive) and that graphs are not well partitioned. (I’ll just mention that if those properties don’t apply, then there may be simpler solutions than what we’ll explore)

To solve this problem, let’s start with the obvious, straight-forward approach: check at every call site. This strategy will look similar in each of the previous approaches we’ve looked at, so I’ll just show the strategy applied to the push-futures approach.

Here’s what the code looks like:

public class ConditionalPushFutures {

public static CompletableFuture<TopLevelResponse> run(Executor executor, TopLevelRequest request,

boolean calculate2, boolean calculateB) {

boolean calculate1 = calculate2 || calculateB;

CompletableFuture<ServiceResponse1> responseFuture1 = calculate1

? CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> Service1.callService(request), executor)

: CompletableFuture.completedFuture(null);

boolean calculateA = calculateB;

CompletableFuture<ServiceResponseA> responseFutureA = calculateA

? CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> ServiceA.callService(request), executor)

: CompletableFuture.completedFuture(null);

CompletableFuture<ServiceResponse2> responseFuture2 = calculate2

? responseFuture1.thenApply(response1 -> Service2.callService(response1))

: CompletableFuture.completedFuture(null);

CompletableFuture<Void> both1AndA = CompletableFuture.allOf(responseFuture1, responseFutureA);

CompletableFuture<ServiceResponseB> responseFutureB = calculateB ? both1AndA.thenApply(ignore -> {

ServiceResponse1 response1 = responseFuture1.join();

ServiceResponseA responseA = responseFutureA.join();

return ServiceB.callService(responseA, response1);

}) : CompletableFuture.completedFuture(null);

CompletableFuture<Void> both2AndB = CompletableFuture.allOf(responseFuture2, responseFutureB);

return both2AndB.thenApply(ignore -> {

ServiceResponse2 response2 = responseFuture2.join();

ServiceResponseB responseB = responseFutureB.join();

return GetTopLevelResponse.getResponse(response2, responseB);

});

}

}

The decision about whether to include Service2 or ServiceB in the overall response has proliferated down to every level. That’s going to happen with any approach we take if we really want to avoid service calls. Still, there are a couple of issues revolving around the way the proliferation happens.

First off, each call knows how it’s being consumed. You can tell by the way each calculateX is initialized. E.g. the call to Service1 knows that it’s consumed by both Service2 and ServiceB; while the call to ServiceA knows it’s only consumed by ServiceB. This is exposing the internals of how Service2 and ServiceB work. You would ideally want that information encapsulated along with those services, to help with evolution over time.

Second, although this example is too simple to see, imagine that calculate2 and calculateB weren’t provided externally by callers but internally based on the results of other calls in the graph. So, instead of being simple booleans, these values would be determined by their own nodes in the dependency graph. This introduces potential latency inefficiencies. E.g. calculate1 depends on calculate2 or calculateB. That means we only know whether to calculate1 when the slowest of calculate2 and calculateB is finished. If one of them had finished early with a value of “true”, we could have started right at that point instead and finished earlier.

Memoization With Arguments

To solve the issues with the previous approach, we can make use of memoization. This strategy will allow us to keep consumption decisions together with consumers and to short-circuit conditions to get them started faster… all while continuing to call services only once.

Here’s what the code looks like:

public class ConditionalMemoizationWithArgumentsPushFutures {

public static CompletableFuture<TopLevelResponse> run(Executor executor, TopLevelRequest request,

boolean calculate2, boolean calculateB) {

ConcurrentHashMap<Object, Object> memory = new ConcurrentHashMap<>();

CompletableFuture<ServiceResponse2> responseFuture2 = calculate2 ? run2(executor, request, memory)

: CompletableFuture.completedFuture(null);

CompletableFuture<ServiceResponseB> responseFutureB = calculateB ? runB(executor, request, memory)

: CompletableFuture.completedFuture(null);

CompletableFuture<Void> both2AndB = CompletableFuture.allOf(responseFuture2, responseFutureB);

return both2AndB.thenApply(ignore -> {

ServiceResponse2 response2 = responseFuture2.join();

ServiceResponseB responseB = responseFutureB.join();

return GetTopLevelResponse.getResponse(response2, responseB);

});

}

private static CompletableFuture<ServiceResponse2> run2(Executor executor, TopLevelRequest request,

ConcurrentHashMap<Object, Object> memory) {

CompletableFuture<ServiceResponse1> responseFuture1 = computeIfAbsent(memory,

createKey("Service1#callService", request),

() -> CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> Service1.callService(request), executor));

return responseFuture1.thenApply(response1 -> Service2.callService(response1));

}

private static CompletableFuture<ServiceResponseB> runB(Executor executor, TopLevelRequest request,

ConcurrentHashMap<Object, Object> memory) {

CompletableFuture<ServiceResponse1> responseFuture1 = computeIfAbsent(memory,

createKey("Service1#callService", request),

() -> CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> Service1.callService(request), executor));

CompletableFuture<ServiceResponseA> responseFutureA = CompletableFuture

.supplyAsync(() -> ServiceA.callService(request), executor);

CompletableFuture<Void> both1AndA = CompletableFuture.allOf(responseFuture1, responseFutureA);

return both1AndA.thenApply(ignore -> {

ServiceResponse1 response1 = responseFuture1.join();

ServiceResponseA responseA = responseFutureA.join();

return ServiceB.callService(responseA, response1);

});

}

// Suppress justification: we only insert values into the map if they're compatible with T

@SuppressWarnings("unchecked")

private static <T> T computeIfAbsent(ConcurrentHashMap<Object, Object> memory, Object key, Supplier<T> supplier) {

return (T) memory.computeIfAbsent(key, ignore -> supplier.get());

}

private static Object createKey(String ClassAndMethod, Object... arguments) {

// Placeholder: imagine we implement this to return a unique key given the arguments

return null;

}

}

Here, we pass around a ConcurrentHashMap memory to memoize calls to Service1 (the only service that needs it in this example, but theoretically, it would be applied everywhere). Doing this has allowed us to express the algorithm in terms of direct consumers and dependencies, rather than in a procedural, step-wise, overall-graph fashion. E.g. the top-level run method talks about running only Service2 and ServiceB, its direct dependencies, with no mention of Service1 and ServiceA, which it knows nothing about. The running of Service2 and ServiceB are completely independent of one another (except that they use the same memory to execute Service1).

There are a couple of issue around this approach. First, we have the access of the shared ConcurrentHashMap by multiple threads, which involves coordination and prevents true independence. This property will inherent in any memoization-based approach. Second, the arguments necessary for the lowest layers of the graph need to be ferried along through. The above example doesn’t highlight this very well since, for example, Service1 uses the same request object as all the other services. Imagine, though, if Service1 needed something completely separate, something that Service2 and ServiceB (its consumers) didn’t need at all. The running of Service2 and ServiceB would still need this extra something, in order to pass it along to the call to Service1. Third, we’re using arguments to perform the memomization. As mentioned in the memoization wiki, this can lead to problems if multiple callers accidentally construct different arguments, leading to separate calls for what should be the same call.

Memoization Without Arguments

One mitigation mentioned in the memoization wiki was the idea of using 0 arguments for memoization. That’s what the following approach does.

Here’s what the code looks like:

public class ConditionalMemoizationNoArgumentPushFutures {

public static CompletableFuture<TopLevelResponse> run(Executor executor, TopLevelRequest request,

boolean calculate2, boolean calculateB) {

Supplier<CompletableFuture<ServiceResponse1>> unmemoizedResponseFuture1Supplier = () -> CompletableFuture

.supplyAsync(() -> Service1.callService(request), executor);

Supplier<CompletableFuture<ServiceResponse1>> memoizedResponseFuture1Supplier = memoize(

unmemoizedResponseFuture1Supplier);

CompletableFuture<ServiceResponse2> responseFuture2 = calculate2

? run2(executor, request, memoizedResponseFuture1Supplier)

: CompletableFuture.completedFuture(null);

CompletableFuture<ServiceResponseB> responseFutureB = calculateB

? runB(executor, request, memoizedResponseFuture1Supplier)

: CompletableFuture.completedFuture(null);

CompletableFuture<Void> both2AndB = CompletableFuture.allOf(responseFuture2, responseFutureB);

return both2AndB.thenApply(ignore -> {

ServiceResponse2 response2 = responseFuture2.join();

ServiceResponseB responseB = responseFutureB.join();

return GetTopLevelResponse.getResponse(response2, responseB);

});

}

private static CompletableFuture<ServiceResponse2> run2(Executor executor, TopLevelRequest request,

Supplier<CompletableFuture<ServiceResponse1>> responseFuture1Supplier) {

CompletableFuture<ServiceResponse1> responseFuture1 = responseFuture1Supplier.get();

return responseFuture1.thenApply(response1 -> Service2.callService(response1));

}

private static CompletableFuture<ServiceResponseB> runB(Executor executor, TopLevelRequest request,

Supplier<CompletableFuture<ServiceResponse1>> responseFuture1Supplier) {

CompletableFuture<ServiceResponse1> responseFuture1 = responseFuture1Supplier.get();

CompletableFuture<ServiceResponseA> responseFutureA = CompletableFuture

.supplyAsync(() -> ServiceA.callService(request), executor);

CompletableFuture<Void> both1AndA = CompletableFuture.allOf(responseFuture1, responseFutureA);

return both1AndA.thenApply(ignore -> {

ServiceResponse1 response1 = responseFuture1.join();

ServiceResponseA responseA = responseFutureA.join();

return ServiceB.callService(responseA, response1);

});

}

private static <T> Supplier<T> memoize(Supplier<T> supplier) {

// Placeholder: imagine we implement this to return a memoized version of supplier

return null;

}

}

Instead of memoizing based on the arguments to each service call, we create a memoized supplier for the service call and pass that along: we define centrally what it means to call Service1, including its arguments, and then share that definition with potential consumers. Otherwise, the approach is the same.

This change can be viewed as either a plus or minus. On the minus side, the run method now knows what it means to run Service1, whereas it knew nothing of that before. On the plus side, the calling of Service1 is now centrally defined and will be consistent for all consumers.

Aggra

Aggra takes the previous approach to the extreme, creating an entire framework to define dependency graph nodes of memoized suppliers based on push-based futures connected into callable graphs. This approach is complex and so isn’t for everybody, as we’ve seen. Let’s take another look at the important properties that got us here to help you decide if it’s for you:

- Latency – we wanted to optimize latency when calling nodes in the graph. We wanted to optimize as far as we could go, beyond any phase-based approach.

- Dependency-based – we wanted to avoid the grouping headaches involved with phase-based approaches, instead executing nodes based on their dependency structure alone.

- Threads – we wanted to make optimal usage of threads, avoiding any thread idling while waiting for a future to finish.

- Debugging – we wanted to improve on the debugging that push-based futures provide (which the Aggra framework does, although not discussed in this wiki).

- Conditionals – we wanted to be able to support conditional execution of nodes in the graph.

- Single call – we only wanted to execute nodes once for a given overall graph call, presumably because nodes are expensive in some way.

- Modular – we wanted to encapsulate consumer relationships in the consumers themselves when defining conditional relationships, rather than externalizing those definitions.

- Internal – we wanted to be able to support internal conditions (i.e. conditions whose value is determined as part of the graph itself)

- Arbitrarily partitioned – we wanted to be able to support a graph with arbitrary partitioning (i.e. one where multiple conditions may apply to parts of the graph).

- Latency – we wanted to be able to short-circuit conditions in order to execute conditional nodes as quickly as possible.

- Memoization – we wanted to use 0-argument memoization to avoid pitfalls we’ve seen with memoization previously.