aggra-guide

Basics

This wiki walks through the basic building blocks of Aggra: data dependency graphs, call propagation, and memory.

Data Dependency Graph

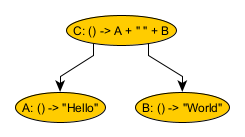

Agga models programs as data dependency graphs: directed acyclic graphs where each node represents a value-returning function and “points” to other dependency nodes whose data it needs to execute its inherent functionality. To demonstrate, let’s start with a simple example:

This graph has three different nodes:

- Node A depends on nothing and produces the string “Hello”

- Node B depends on nothing and produces the string “World”

- Node C depends on both nodes A and B, calling them, appending the results with a space, and yielding “Hello World”.

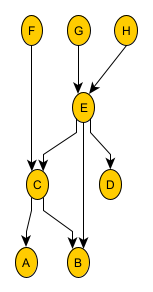

Below is a more abstract and complicated graph that will be used in future examples. As before, arrows point from consumer nodes to dependency nodes.

This graph helps highlight the somewhat-arbitrary dependencies nodes can have: nodes can have multiple dependencies and multiple consumers as well. The only forbidden types of dependencies are cyclic, either transiently through nodes or direct/self cycles. (Aggra prevents Nodes from being built with static cyclic relationships, and has multiple protections in place to avoid dynamic cycles during calls. That said, make sure to read javadoc and follow expected usage patterns to avoid those dynamic cycles completely; otherwise, the graph will stall as a node will wait for itself to finish before finishing.)

Concretely, here are the steps that you take in order to create and call nodes in a graph:

- Create a set of Node objects.

- Create a Graph object with a set of Nodes you consider to be “roots” of the Graph. This Graph object is supposed to exist across multiple overall requests.

- For a given overall request, create a GraphCall object via the Graph you created before. This GraphCall object will exist for the duration of the overall request only.

- Call one or more of the root Nodes in the Graph via the GraphCall object you created. Each node call will result in a Reply object.

- Once you’re done calling all root Nodes, (weakly) close the GraphCall object. This will return a CompletableFuture that will complete when all nodes in the GraphCall have finished. Wait for this Future to complete, read all of your Replys, construct your overall response, and then return it.

The full-fledged Hello World code example demonstrates this process in full.

Call Propagation

Graphs are static: they’re supposed to exist for multiple calls/requests to the graph. Nodes only model behavior and dependencies: they don’t store any request-dependent state/results. Instead, results are stored inside of “memory” instances, which are created on a per-request basis and passed around between nodes. These memories memoize the results from each node, making sure that each node’s functionality is run only once and always returning that result to consumers. In addition, individual nodes are only run if their consumers call them, whether that consumer is another node or an external caller.

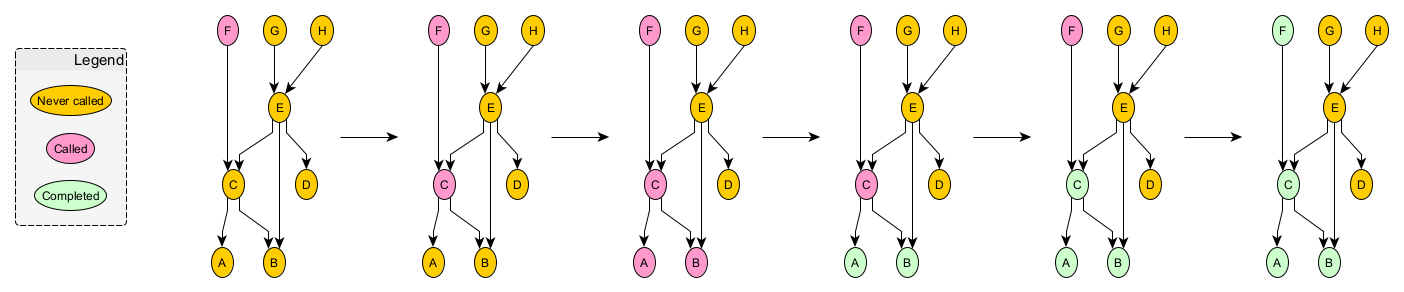

To help cement this idea, let’s take a look at the previous graph as one of its nodes (F) is called, that call is propagated, and results are computed.

Orange nodes are nodes that have never been called, red nodes are nodes that have been called but aren’t complete yet, and green nodes are nodes that are complete. Note: the applied coloring is only a visual aid. Nodes themselves do not store state or change. Rather, state/results is/are stored in the memory instance passed between nodes. So, the best way to view this sequence is how a specific memory instance sees the graph.

In the first picture of the sequence, node F is called. Node F can’t complete without the results from node C, so in the next picture, we see that node F has called node C. Similarly, in the next picture, we see that node C has called nodes A and B. At this point, nodes A and B are leaf nodes and can complete, which we see in the next picture. Now that nodes A and B, the dependencies of C, are complete, node C itself can complete. Finally, we see that node F can complete since C is complete. At the end of the sequence, the call to node F can return with the result of F’s function.

There are a couple of call-outs here. First, it’s assumed that node F will always call node C and that node C will always call both nodes A and B. This does not necessarily have to be true. Nodes F and C can be more selective about who they call. In other words, nodes are allowed to prune their dependency calls when they want to. This property is what allows Aggra to model conditional relationships. Second, nodes G, H, E, and D are never called, because no consumer has called them, either externally or through another node. Third, we can see the call propagate down a dependency graph and how the results then propagate back up it.

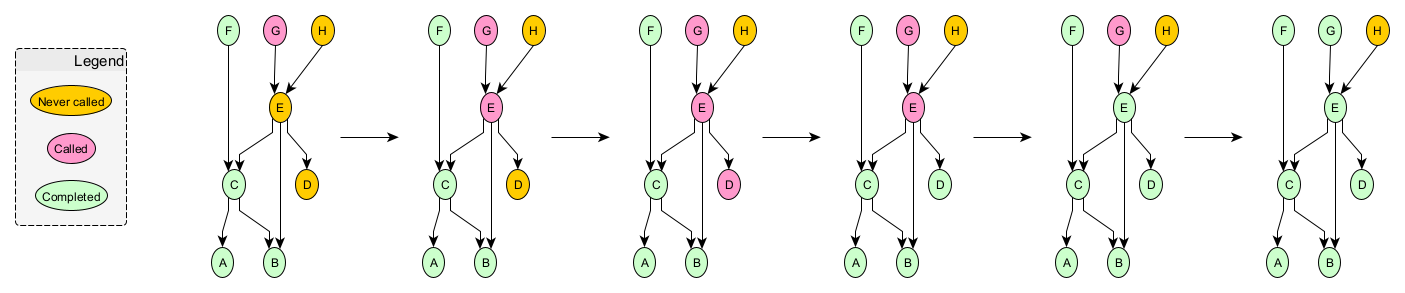

A slightly more complicated example would be if nodes G and/or H were called as well as node F. That example would highlight the memoizing functionality of nodes/memory. In fact, there’s nothing preventing that from happening at the end of the sequence above: nodes G and/or H could be called at the same time as node F or at completely different times. As long as the memory instance was the same, the end result would be the same as well. Let’s take a look at that extension: node G being called with the same memory instance at the end of the sequence above.

The beginning of this additional sequence looks the same as before with just node G being called. In the next picture, node G has called E. Then, E has called both C and D; however, since node C is already complete, it remains in that state. This highlights how memoization works relative to a given memory instance: node C has been called multiple times but will only ever be run once and produce a single result. Next, we see node D completing; then E; and finally back up to G.

Memory

The last section gave us a small introduction to memories. Let’s take a closer look at all of the properties and features it provides.

Memoization

Memories memoize the calling of nodes. Aggra creates memories and then passes them around as a part of each node call. When a consumer node calls one of its dependency nodes, Aggra first checks the memory to see if that call has already started before. If so, regardless of whether that call is finished yet, Aggra returns the saved result to the consumer. If not, then Aggra runs the dependency node and inserts the (in-progress or already-finished) result in the memory.

It’s this property of memories that allows graphs to be static. All of the per-request state is saved in the memories passed between nodes.

Inputs

So far, we’ve only considered graphs that are self-contained: there’s no external input from outside of the node graph: leaf nodes somehow produce results on their own from nothing. While this may be true in isolated cases, it’s not the norm: programs almost always require external input. Aggra supports this use case by associating an input with each memory instance. Clients can then build special nodes (called input nodes) that, rather than generating their result from nothing or by calling dependencies, simply return the input provided by the memory passed through it. These nodes, then, “inject” the input into the graph for processing by consumer nodes.

How does a given input node know that its desired input will be present in the memory passed to it? Each Node, in addition to being parameterized by the type of result it returns, is also parameterized by the type of its Memory subclass. That is, Aggra contains an abstract Memory class, which is itself parameterized by input type. When creating a graph, users are required to define a specific Memory subclass to be associated with its nodes. Only memories of that type can be used with the node during execution.

For example, in the Hello World example we went through, we created a HelloWorldMemory, which provides inputs of type String. Nodes in the graph declare themselves to be bound to HelloWorldMemory and so only usable with that type of memory. In this way, its input node is guaranteed to receive a memory with a String; plus, other types of nodes elsewhere in the graph, which depend on the input node either directly or indirectly, are guaranteed to be able to provide the input node what it needs. It’s as if each node in the graph is able to say to consumers “if you give me a String as input, I can provide you with something of type <ReturnType>”; input nodes will use that String directly, whereas other nodes will pass along that memory (with a String) to it dependencies.

Why does this feature require the creation of a specific memory subclass for each graph? It doesn’t. Theoretically, we could have a single, non-abstract Memory class parameterized by input type. We could then parameterize nodes by input type as well (instead of by memory). However, that model wouldn’t be able to provide the kind of guarantees desired for the next feature we’re going to talk about.

(Side note: in other wikis, we’ve talked about how important it is to be able to memoize based on 0-argument functions. How are we able to talk about inputs here? The key is that there’s only one input in play, and it’s associated with the memoization device itself: the memory. So, you could technically say a graph call is memoized relative to a single, overall argument… but this memoization is implicit, and any explicit memoization happens with 0 arguments.)

Hierarchy

In an ideal world, each graph would have a single type of memory associated with it. That’s the simplest type of model. There are two problems with that desire:

- Iteration – Aggra doesn’t allow cycles in dependency graphs… but lots of programs will need to execute a function iteratively with different input.

- Reuse – users might want to reuse one graph as part of another graph.

Aggra solves both problems by arranging memories in a hierachy.

Iteration

Aggra supports iteration by allowing nodes to create new memories, call nodes in those memories, and allow nodes in those memories to access their ancestors. Let’s take a look at an example:

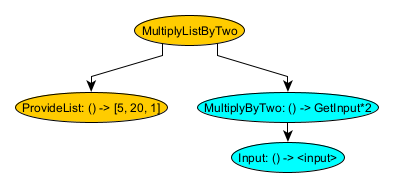

In this dependency graph:

- The color of each graph indicates the memory to which the node belongs. Orange nodes are part of a “parent” memory, while blue nodes are part of a “child” memory.

- MultiplyListByTwo calls ProvideList to get a list of number and then, for each number in the list, creates a new child memory where the input is that number, executes MultiplyByTwo, and then collects each result.

- MultiplyByTwo gets its memory’s input via GetInput and then multiplies that number by 2 to provide an output.

- Because of this logic, MultiplyListByTwo ends up creating 3 child memories, one for each or 5, 20, and 1; and multiplies each by 2; yielding a list of [10, 40, and 2] as its result.

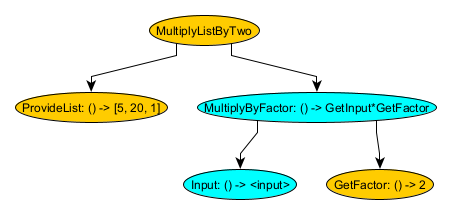

This is a simple example of iteration showing how a parent memory needs to create and then use a child memory. What about if the child memory needs to access its parent memory for some data shared by all child memories? Let’s take a look at this by extending the above child memory to handle arbitrary factors:

In this dependency graph, we’ve factored out the “2” into a new node GetFactor associated with the parent memory (Note: GetFactor still returns 2, so the overall result is the same, but it could be changed in one place to an arbitrary factor).

So now, when MultiplyByFactor is running, it needs to be able to access GetFactor in the same parent memory where it was created. The only way to access request state is through memories. So, how can we make sure that the MultiplyByFactor memory is guaranteed to be able to provide access to its parent MultiplyListByTwo memory? Extrapolating further, we could imagine MultiplyListByTwo having its own parent, and that parent having its own parent, etc. MultiplyByFactor could theoretically need access to any arbitrary ancestor memory. A non-abstract, single Memory class just won’t do since it would be impossible to model an arbitrarily typed hierarchy (“type” as in input type). Instead, this is where the need for user-created Memory subclasses comes from.

The way that Aggra models this situation, the MultiplyByFactor Memory is modeled by the user as a Memory subclass such that it can only be created when all of the ancestor memories it needs access to are available. Furthermore, the MultiplyByFactor Memory subclass will provide accessors for those ancestor Memory instances. This way, users can safely use the MultiplyByFactor Memory with the guarantee that it provides the necessary execution environment. In addition, anyone who creates it, like from the MultiplyListByTwo Memory, must have the necessary pieces available to be able to do so. These properties also make the memories amenable to hierarchy changes, as missing new ancestors will cause compilation errors.

Reuse

Iteration shows the need for user-created Memory subclasses arranged in a hierarchy. The most-straight-forward way to model that would be to limit memories to having a single parent and making sure that children could only be created while running nodes in the parent memory. E.g. this would mean that only nodes associated with the MultiplyListByTwo Memory could create MultiplyByFactor Memories. This scheme would definitely make it easier to check that memories are being used in the correct way. The problem is with reuse.

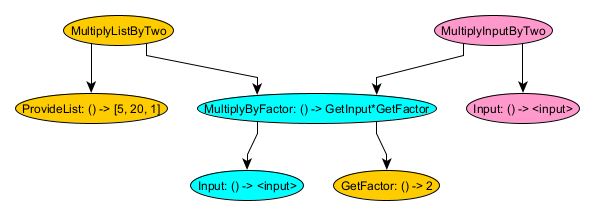

For example, let’s say that someone wants to reuse the MultiplyByFactor nodes.

Here, we’ve got two new nodes from a completely different memory:

- Input – a separate input node that gets the input for that new memory

- MultiplyInputByTwo – node that calls the new input node, creates a new MultiplyByFactor Memory with that input, and then calls MultiplyByFactor. So with an input of, say, 30, MultiplyInputByTwo would yield 60.

This new MultiplyInputByTwo node has no relationship to MultiplyListByTwo and shouldn’t be forced to share the same memory. Instead, it gets its own MultiplyInputByTwo memory. The MultiplyInputByTwo node must still be able to create a MultiplyByFactor memory, and since this depends on a MultiplyInputByTwo Memory, the MultiplyInputByTwo node must be able to provide that, which it can do easily by creating it inline just before it creates the MultiplyByFactor Memory.

In addition, there’s no reason to limit the MultiplyByFactor Memory to depend just on one parent memory directly. It could really just depend on any arbitrary number of parent memories. The only catch is that the nodes that create the MultiplyByFactor Memory must provide all of these ancestor memories at MultiplyByFactor Memory creation time. Perhaps the node can get those from the current running Memory and its ancestors… or perhaps it will create them. It all depends on the usecase and how the node wants the MultiplyByFactor nodes to share memory with other parts of the program.

Although this scheme allows for extreme flexibility and reuse, the cost is that users must make conscious decisions when creating new memories for how to provide the needed ancestors. E.g. if you really want the nodes in the new memory to access pre-existing ancestors but provide a new ancestor instance instead, that will result in unwanted additional node runs. There’s no way for Aggra to provide guiderails here, as there may be some usecases where this is and some where it isn’t appropriate. The power is yours.

Summary

Aggra provides access to external input via memories. Multiple memories can exist for the same graph call, even multiple instances of the same memory in order to implement iteration. Memories are organized in extremely flexible hierachies. Users are responsible for creating Memory subclasses and partitioning their graphs appropriately based on those subclasses. Memories can have multiple parents, grandparents, etc. When creating memories, users must provide access to these ancestors, either through pre-existing instances (perhaps from the memory associated with the current running node or its ancestors) or by creating new ones, depending on how users want their graphs to share memories with other parts of the graph. Be conscious of which decision you make and the implications (i.e. shared node runs or completely new ones).